Pinned

🗽 START HERE: How to join our Group Calls!

We built this community for people who want to talk, not just scroll. The real action happens in our group calls, where we argue ideas in good faith and tackle the week's biggest global events. Here is how you can participate: 🔥 1. Open Calls These are our public town halls. Open to everyone. Whether you want to take the stage to challenge a point or just listen in, this is the "public square." 💎2. Premium Calls For members who want to go deeper. These calls are exclusive to our supporters and offer a space for more focused discussion and priority access. - 📅 Check the Schedule & Join Here: https://www.skool.com/libertypolitics/calendar - 💎 Become a Premium Member: https://www.skool.com/libertypolitics/plans Heads up: We believe these conversations are worth sharing! Our group calls are recorded and may be posted to our social media channels. By joining the stage, you’re helping us bring these important discussions to a larger audience. By participating in group calls and voice discussions, you consent to being recorded. 👋 New to the group? Say hello! We want to get to know you. Drop a comment below to introduce yourself. Tell us where you're from and what you like to do for fun (outside of arguing politics!). Welcome to the community!

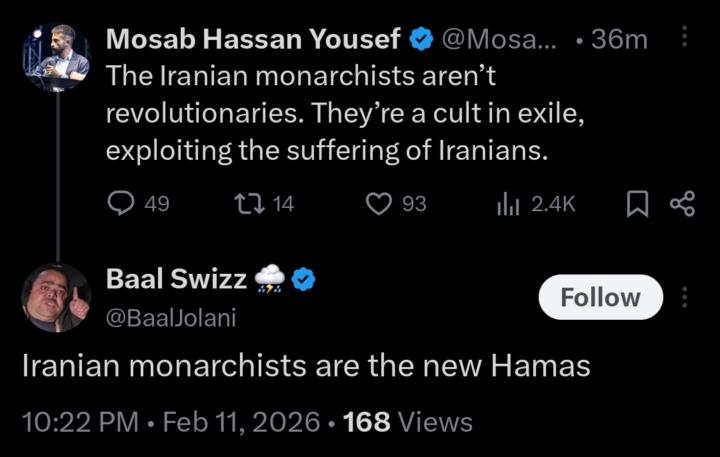

Umm.

Can someone tell me how I'm supposed to feel and act when I see shit like this as an Iranian? This is the dangerous door that Mosab has opened. We are witnessing the propaganda unfold right in front of us.

Urgent: an assassination a few minutes ago in the middle of Tehran

Iranian news sources stated that the person killed is a high level chief of the IRGC. (Translation of the arabic message) I personally would dare say that was the work of Israel. They have done that before. https://x.com/i/status/2021685185541034215 I did not find this news on my other news sites for now.

From cyrus to the rising sun

Hi everyone, i been working on this song for a while with the help of ai. Finally finished it today and its ready to watch on YouTube. I hope everyone likes it. Let me know your thoughts. https://youtu.be/-BBLpb7O640?si=WP1ObtlqRfTb2Fww

1-30 of 1,720

skool.com/libertypolitics

Talk politics with others who care, in live calls and community posts. Share your views, ask questions, or just listen in.

Powered by