16d • General discussion

WHY PERFORMANCE IS ABOUT TRANSITIONS, NOT INTENSITY

Most people think performance improves by pushing harder. More intensity, more volume, more effort, more stimulation. That belief makes sense because intensity is visible. You can see heavy weights, fast running, deep breathing, sweat, and fatigue. What you cannot see is what actually determines whether the body adapts or breaks down. That hidden factor is how well the body handles transitions.

Biology does not reward force. It rewards coordination. At every level of the body, from a single cell to the entire nervous system, health and performance depend on how smoothly systems shift from one state to another. These shifts include rest to effort, effort to recovery, fed to fasted, stress to calm, inflammation to healing, and sleep to wakefulness. The quality of these transitions determines whether the system becomes stronger or weaker over time.

A transition in biology is any moment when demand changes faster than structure can adapt. When exercise begins, muscles suddenly require more energy. When exercise stops, energy demand suddenly drops. When food is eaten, nutrients flood the bloodstream. When fasting occurs, energy must be mobilized internally. When stress hormones rise, immune and metabolic priorities shift. These changes are not steady states. They are moments of adjustment, and they are where the system is most vulnerable.

Most people misunderstand how energy works in the body. Energy is not something you simply have or run out of. Energy is controlled flow. At the cellular level, this flow is managed by mitochondria. Mitochondria are often called powerhouses, but a better way to understand them is as traffic controllers. Their job is not just to make energy, but to regulate how electrons move through a tightly controlled system.

Electrons enter mitochondria from the breakdown of food and stored fuels. These electrons move through a series of protein complexes called the electron transport chain. As electrons move through this chain, energy is released in a controlled way to produce ATP, the molecule used to perform work. ATP is not the goal. It is the result of proper electron flow. When electron flow is smooth, energy production is clean and signaling is preserved. When electron flow becomes congested, problems arise.

Intensity increases demand very quickly. When demand increases faster than the mitochondria can adapt, electrons flood into the system faster than they can be processed. This creates congestion, similar to too many cars entering a highway at once. When electrons back up, they are more likely to leak out of the system and react with oxygen. This creates reactive oxygen species, often called ROS.

ROS are commonly labeled as harmful, but this is incomplete. ROS are signals. In the right amount and at the right time, they tell the cell that something has changed and that adaptation is needed. This signaling is how mitochondria become more efficient and muscles grow stronger. Problems arise when ROS appear in excess during poorly managed transitions. In that case, ROS cause damage instead of adaptation. The difference is timing and context, not simply quantity.

Most cellular damage does not happen during peak output. It happens during acceleration. Imagine revving a car engine instantly while the oil is still cold. The damage does not occur because the engine runs fast, but because lubrication and alignment lag behind acceleration. The same principle applies to cells. When exercise begins, calcium floods muscle cells, oxygen use increases, and fuel delivery shifts rapidly. If the mitochondrial structure is not ready, electrons pile up before the system stabilizes. This is when oxidative stress spikes.

This explains why warm-ups matter. Warm-ups are not just for muscles and joints. They prepare mitochondria to handle increased electron flow smoothly. Gradual increases in demand allow membranes, enzymes, and signaling systems to adjust without congestion.

Inside mitochondria are folded structures called cristae. These folds organize the electron transport chain and determine how efficiently electrons move. Cristae are not fixed. They reshape themselves in response to demand. When cristae are flexible, mitochondria adapt quickly during transitions. When cristae are rigid, electrons struggle to move efficiently, especially when demand changes quickly.

Rigid cristae do not necessarily stop ATP production. This is why people can feel functional while still failing to adapt. They may have enough energy to get through the day, but the quality of signaling needed for improvement is lost. Over time, this leads to stagnation.

Cristae flexibility depends heavily on the health of mitochondrial membranes. These membranes are not passive barriers. They are dynamic platforms where proteins move, interact, and respond to signals. If membranes are stiff, crowded, or damaged, these interactions slow down. This creates friction during transitions.

Certain membrane lipids help maintain flexibility and resilience. Some lipids allow proteins to move freely, while others absorb brief oxidative spikes during rapid transitions. These lipids act like shock absorbers. If shock absorbers are worn out, even a powerful engine cannot deliver smooth performance.

One class of lipids often misunderstood is plasmalogens. Plasmalogens are not simply antioxidants that remove oxidative stress. Their real role is to buffer timing. They absorb short bursts of oxidation during transitions and then regenerate. This allows signaling to occur without structural damage. They are especially important during transitions such as waking up, starting exercise, immune activation, and metabolic shifts.

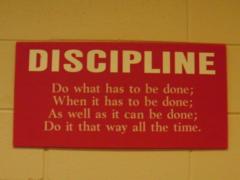

This distinction matters because stress itself is not the enemy. Stress is how adaptation occurs. Eliminating stress eliminates progress. The goal is not to avoid stress, but to manage its timing and intensity so the system can respond appropriately.

Redox state refers to the balance between electrons entering and leaving a system. Too oxidized means electrons move too fast and signals burn out. Too reduced means electrons back up and stall the system. Many people who feel chronically fatigued are not depleted. They are congested. Adding antioxidants in this state can make things worse by slowing electron flow even further. What the system needs is improved flow, not suppression.

Lactate is another molecule often misunderstood. Lactate is not waste. It is a signaling molecule and an energy shuttle. It allows tissues to communicate how hard they are working and helps redistribute fuel throughout the body. What matters is not how much lactate is produced, but how efficiently it is cleared and reused. Fast clearance reflects smooth transitions and healthy mitochondria. Slow clearance reflects congestion.

In strength training, growth does not depend on how hard one set feels. It depends on how well mitochondrial efficiency is maintained across multiple sets. As fatigue accumulates, electron congestion increases and signaling quality declines. If set-to-set efficiency collapses, additional volume becomes unproductive. Managing rest intervals and training density is really about protecting transition quality.

For clinicians, this perspective shifts focus away from static lab values alone. Many patients appear normal at rest but struggle during transitions. They may feel wired but tired, inflamed without markers, or stuck despite normal test results. Supporting membranes, respecting circadian timing, and avoiding indiscriminate antioxidant use can restore transition capacity and improve outcomes.

For strength coaches, performance is not about how hard athletes are pushed. It is about how cleanly they accelerate and recover. Gradual warm-ups, intelligent load progression, appropriate rest intervals, and recovery-based volume management all support mitochondrial transitions. When transitions are respected, intensity becomes productive instead of destructive.

The central idea is simple. Performance does not fail because people lack effort. It fails because transitions are rushed. Mitochondria do not exist to generate power alone. They exist to coordinate flow. When transitions are smooth, adaptation follows naturally. When transitions are chaotic, intensity turns into damage. Training transitions is what allows intensity to work instead of harm.

21

8 comments

skool.com/castore-built-to-adapt-7414

Where science meets results. Learn peptides, training, recovery & more. No ego, no fluff—just smarter bodies, better minds, built to adapt.

Powered by