Pinned

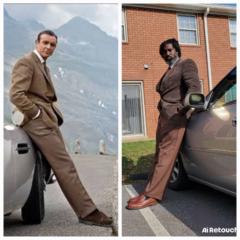

HE'S ALIVE........ (Mad Scientist Laugh)

I have resurrected Al Voss and will vanquish his evil twin soon........Down with the Farklemiser.

Pinned

Evil Twin

I see my evil twin made it in the room. The room might need an exorcism now.

Pinned

🕯 Yuletide & Festive Loneliness 🥂

Gentlemen, Dames As the tinsel goes up, so too — one observes — does the general sense of existential despair. It’s quite all right to acknowledge this. We all feel it. December, for all its glitter and glühwein, is a treacherous month for the solitary man. The shops overflow with couples in matching knitwear. Invitations abound, yet somehow all lead to events titled “Merry and Married.” Even the wine begins to taste smug — much like those Christmas cards, plastered with faux-happy family photos and a Labrador in antlers. And to compound the matter — as if the universe were actively conspiring — His Grace’s football (“soccer”) team has entered into what can only be described as a tactical winter hibernation, languishing at the wrong end of the Premier League, with a festive fixture list that promises further psychological ruin. It is, one might say, a perilous time for morale. So let it be known: Christmas is not, in fact, the most wonderful time of the year. For many of us, it is a brutal reminder that one is not in Saint‑Tropez, not in love, and not — despite heroic efforts — anywhere near the top four. So what is a gentleman to do? He is to rally. He is to send for cigars. He is to check on his comrades. He is to pour a generous port and raise it — not to sentiment, but to sovereignty. The Society of Ordinary Gentlemen should hold the line this season, and I encourage us all to connect more. I shall be available for chats, dispatches, and perhaps a festive conference call — accompanied by an iced bottle of Veuve Clicquot from my Spanish hacienda, where I shall be restoring myself, most likely by the pool. This is our Dunkirk. So if you see a fellow member adrift this December — do not let him drift. Send a message. Extend a hand. After all, a gentleman does not let another gentleman go mad alone in December. Rene

Dwight D. Eisenhower, an exemplar of a gentleman

A gentleman is not defined by lineage, privilege, or affectation, but by the interior discipline with which he holds power, difference, and responsibility. He is not made by the adherence to red pill alpha male drivel or popsych reductionism (e.g. O. Taraban). He is a man whose presence confers calm rather than anxiety, whose authority does not require intimidation, and whose manners are not ornamental but ethical—visible signs of respect for the dignity of others. In moments of conflict, the gentleman distinguishes himself by restraint; in moments of victory, by magnanimity. He understands that force may compel compliance, but only character can restore trust. It is in this rarer, more exacting register that Dwight David Eisenhower emerges—not as a conqueror intoxicated by triumph (i.e. Patton), but as a reconciler whose composure, social intelligence, and quiet elegance made cooperation possible among allies and adversaries alike. Eisenhower’s greatness lies less in the battles he oversaw than in the morality of his leadership: a steadiness that unified fractured wills, a grace that translated across hostility, and a dignity that rendered peace thinkable after war. Dwight Eisenhower demonstrated a paragon virtue, rare in our current zeitgeist – that of reconciliation. Unbeknownst to many, unless a fellow avid historian, Eisenhower had a much harder time working with and facilitating the cooperation of the Allied nations, than he did encountering the enemy on the battlefield. Eisenhower’s command was burdened by a moral problem: he was tasked with unifying men and nations whose suspicions of one another often ran deeper than their hostility toward the Axis. The Allied coalition was not a natural harmony – “friendly” would be an overstatement - but a volatile convergence of wounded pride, divergent strategic visions, and unresolved historical grievances. British caution, American assertiveness and insistent, French humiliation, and competing egos among senior commanders produced a latent instability that threatened to fracture unity from within. Eisenhower understood that no amount of tactical brilliance could compensate for moral disintegration among allies. The temptation before him was real and constant—to dominate rather than mediate, to silence rather than reconcile, to impose authority by fear rather than earn it through trust. That he consistently resisted this temptation reveals the ethical seriousness of his command. He grasped that the integrity of the coalition was not a secondary concern but the very condition of victory and the seed for an enduring peace.

Al Voss is Back

I was locked out of my account. @Stephen Arnold persisted with Skool in Australia to get everything corrected. If my humor doesn't offend you, I'll try harder. Kinda like when you don't hear the train whistle. The train isn't horny. That's why I never liked Asian brothels, an hour later your horny again. Speaking of horny...

1-30 of 717

skool.com/society-of-ordinary-gentlemen

The Society of Ordinary Gentlemen is a community of Gents and Ladies who share ideas from the mundane to the masterful without trolls and scammers.

Powered by