Write something

Food for Faith 2/13/26: Jesus and Nervous System Regulation

Jesus didn’t “push through” stress. He withdrew. Before big decisions. After emotional intensity. In grief. Under pressure. He went away to pray. To be still. To restore. That wasn’t weakness. That was wisdom. Modern neuroscience calls it nervous system regulation. Scripture simply shows us the pattern. A dysregulated nervous system can’t hear clearly. Can’t respond wisely. Can’t sustain peace. Stillness wasn’t separate from His mission. It sustained it. If you’re anxious, overwhelmed, overstimulated, exhausted… Maybe the next faithful step isn’t doing more. Maybe it’s withdrawing — like He did. This is what we explore inside the NeuroTerrain Mental Health course: How faith, physiology, and healing were never meant to be separate. 🔗 Join us here: https://www.skool.com/bedrock-nation-8489/classroom/ab34cae5 Peace starts in the nervous system. And Jesus showed us the way. #FoodForFaith #NeuroTerrain #FaithAndMentalHealth #NervousSystemHealing #ChristianWellness #BedrockNation

0

0

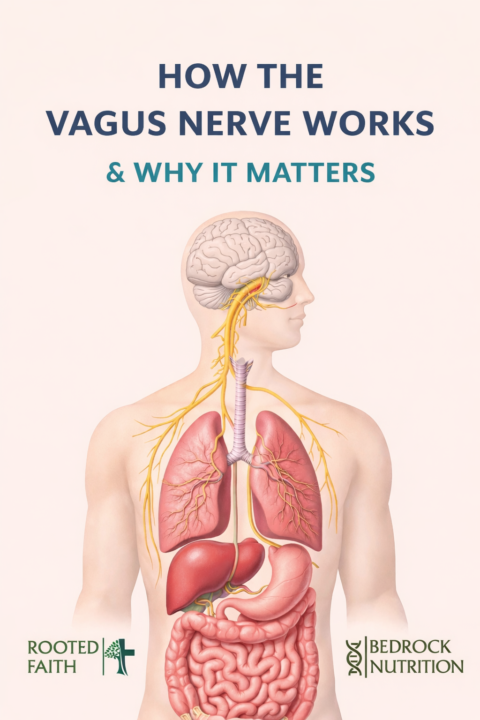

How the Vagus Nerve Works

How the brain talks to the immune system (and why this changes everything) If you’ve ever noticed that stress makes your gut worse, your sleep worse, your mood shorter, and your inflammation louder… you’re not imagining it. One of the main “communication highways” tying all of that together is the vagus nerve—the longest cranial nerve in the body, connecting the brainstem to the heart, lungs, digestive tract, and immune signaling hubs. What the vagus nerve does (in plain English) Think of the vagus nerve as a two-way radio between your brain and your body: - It carries information UP to the brain about what’s happening in your gut, organs, and immune system. - It carries signals DOWN from the brain that influence heart rate, digestion, inflammation, and recovery. This is why vagal tone (how well this system “communicates”) is so closely tied to stress resilience, digestion, mood stability, immune balance, and inflammation. The inflammatory reflex The brain’s built-in “inflammation brake” Researchers describe a specific neuro-immune circuit called the inflammatory reflex—a pathway where the nervous system can turn down inflammatory cytokine output in the body. Here’s the simplified sequence (matching the concept shown in that diagram): 1) The signal starts in the brainstem When the vagus nerve is activated (think: slow breathing, relaxation response), the brain sends output down vagal pathways that can influence immune signaling. 2) The spleen acts like a relay station The vagus nerve interfaces with splenic immune circuitry through the splenic nerve. In this pathway, signaling ultimately leads to norepinephrine release in the spleen, which then activates a specific subset of T-cells. 3) Immune T-cells release acetylcholine This is one of the coolest parts: certain T-cells can produce acetylcholine, which functions like the “final messenger” in this anti-inflammatory circuit. 4) Acetylcholine tells macrophages to “stand down” Acetylcholine binds to receptors (including α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors) on macrophages and can reduce inflammatory cytokine release, including TNF-α in experimental models.

Food For Faith is Back for 2026 - talking about goals!

A little longer than my usual 2 minutes - but just getting us all back on track!

5

0

Discipline as Stewardship

I feel like I needed this reminder today, and maybe you did also: Christians should be some of the most disciplined people on the planet. Not because we worship fitness. Not because we’re trying to impress anyone. But because stewardship is commanded. Your body is not a prop. It’s not “yours to do whatever with.” It’s a living offering. A tool. A temple. A testimony. (1 Cor 6:19–20) And discipline isn’t “extra credit.” It’s biblical. Paul literally says he disciplines his body and keeps it under control. (1 Cor 9:27) We’re told to train—and yes, physical training has value. (1 Tim 4:7–8) So let me say this plainly: If food controls you, something is out of order. If cravings lead you, you’re not leading. If you’re always “starting Monday,” you’re not lacking information—you’re lacking structure. And before anyone says, “But God cares more about the heart” … Correct. And He expects the body to follow. This isn’t about vanity. It’s about authority. A body ruled by appetite cannot be fully surrendered. 3 simple lines in the sand (start today): 1. Protein first (break the sugar cycle before it starts). 2. Move daily (even if it’s a walk—obedience over intensity). 3. Remove the trigger foods you “can’t moderate.” (If it triggers you, it owns you.) If you’re ready to stop making excuses and start building habits that honor God— Subscribe so you don’t miss Food for Faith Friday + weekly training Below is a "starter checklist"

The biochemistry of prayer

✨ Prayer— It’s God-Designed Biochemistry ✨ Here’s what actually happens in your body when you pray: ⸻ 1. Prayer calms the fear centers of your brain. When you pray, activity in your amygdala — the part of your brain responsible for fear and “fight or flight” — drops. Studies show that just 8 weeks of daily prayer or meditation can lower cortisol by up to 25%. Your brain shifts out of survival mode… and into healing mode. This is why you feel yourself exhale in God’s presence. Your body finally believes, “I’m safe.” ⸻ 2. Prayer strengthens your heart’s resilience. During prayer, your heart rate syncs with your breathing, increasing HRV (heart rate variability) — one of the best markers of stress resilience and longevity. Your body literally learns flexibility. Your heart and breath come into rhythm. Your brain receives the message: “You’re carried. You’re protected.” That isn’t mysticism — it’s physiology created by God. ⸻ 3. Prayer activates your parasympathetic nervous system. Harvard researchers call this “the relaxation response.” The Bible calls it peace that surpasses understanding. When you pray: • inflammation decreases • blood pressure stabilizes • healing pathways activate Ancient believers called it “humility.” Modern science calls it “anti-stress neural circuitry.” ⸻ 4. Prayer rewires your mind. Prayer isn’t just calming — it reshapes your interpretation of stress. Challenges stop feeling like threats and begin to feel like assignments. People who pray consistently are significantly more resilient after grief, trauma, or loss. Because prayer is cognitive reframing with God at the center. Your prayers become your new internal dialogue. ⸻ 5. Collective prayer changes your chemistry. When we pray together, oxytocin — the “connection hormone” — rises. Loneliness shifts into belonging. Dozens of voices become one family. This is one reason people with a deep faith live, on average, 5–7 years longer. Not because life is easier… but because community heals deeper than any medication ever could.

1-10 of 10

powered by

skool.com/bedrock-nation-8489

Free wellness community for faith based living, functional health and real connection - off social media, rooted in purpose - learn, grow and heal.

Suggested communities

Powered by