Activity

Mon

Wed

Fri

Sun

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Jan

Feb

What is this?

Less

More

Memberships

Free Skool Course

44.7k members • Free

Conscious Creator Club

1.7k members • Free

The Primal Resistance

1k members • $47/month

Truth Seekers Society 🆓

10.4k members • Free

New Earth Community

4.9k members • Free

69 contributions to New Earth Community

No Fluff. Just be Human.

The most spiritual thing you can do for yourself is be fucking human in your most human way. As simple as that. We tend to overcomplicate things, and in doing so, we move further away from the very point of existence. Yes, it’s nice to know you’ve lived lifetimes. Yes, it can feel validating to recognize that you know things before you understand why you know them or where they came from. But all of these are only guidelines—breadcrumbs meant to lead you back to yourself. Less identity. More embodiment. Life is meant to be lived in its fullness—with all the stillness and all the harshness it offers. It is not easy to live within the matrix without being drowned by it. There are days you die a little—let it. Feel it. But don’t succumb to it. And then the next day, you come back swinging like nothing happened. Awakening is not glamorous. It is a tedious, grueling process of highs and lows until, slowly, you become more regulated, more attuned, less scattered. No one is a special unicorn here. Everyone carries unique gifts for their own purpose. Everyone is on their own adventure. No one has the right to judge another’s path—awake or still sleeping. Separation of identity is what divided us. It’s time to dismantle that illusion now. Once you begin to master yourself, navigating life becomes deeply interesting—not because it gets easier, but because it gets clearer. I used to think awareness made me different. It doesn’t. It just makes you responsible. Do it for yourself, not for others. Do it tired. Do it broken. Do it angry. But do it anyway. One day at a time—until you arrive at a place where you feel free, content, and at peace. Sometimes words fail to capture what essence already knows. Let your presence be felt through who you are, not just through what you say you are. Don’t pour from an empty cup. Let your overflow fill the empty glass of others. Learn when to step back. Sometimes containment in stillness is more powerful than noise. You may think you are not contributing, but often you are contributing more efficiently in silence.

1 like • 6d

@Angelica Carrier Thanks! Yes I wrote it here and because it was still on my mind I shared it today on the call. I never really told that story, because I felt that it would invalidate my intentions. But I see now perhaps I should get over that, if the story has a message to pass, then it’s not about me, it’s about the message. That this should just be normal and totally unremarkable. Thanks for your comment, it really means a lot to me.

2 likes • 6d

@El Rome Hi. Thanks. 🙏. And… yes it is amazing sometimes how path meet. I didn’t know it would make any difference to anyone, today just felt I should share this story, because it was a really important thing that happened in my life, and I don’t really have said it to other people. Now I remember some people, that said something or did something, had no intention that they touched me deeply and I never saw again. They have no idea how much that meant to me.

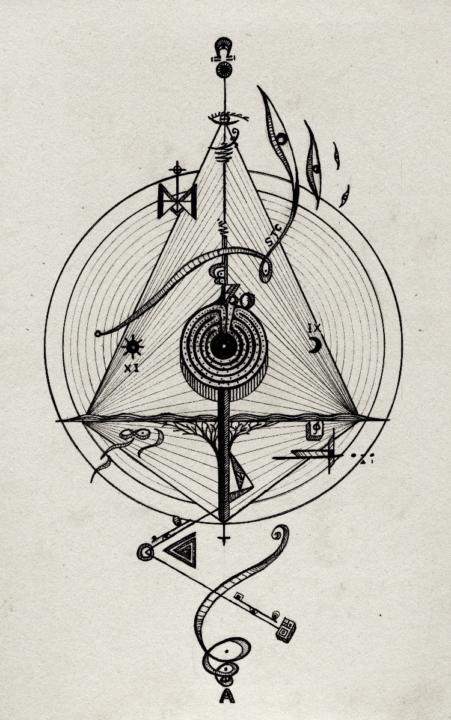

Solar Cross Calendar Geometry

Sharing a post I made about the mathematical and geometric foundation of the Solar Cross Calendar. It’s a bit long and geeky, but it’s meant to ground and clarify the idea. https://www.instagram.com/p/DUODPMhjHI_/?igsh=MTljMGpnY2tqb3oweA== If anyone wants to read the full article you can find it for free on Substack. https://substack.com/@alexdimitriadis/note/p-186495158?r=7a26z1&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=notes-share-action Any constructive feedback, comments, questions, would be appreciated. Thanks Alex

Give me opinions... Interested in feedback.

This is not ‘we are evil’ and not ‘I’m pure.’ This is adult responsibility. I want to speak honestly, without pretending I’m outside the system. I’m not. I use its money. I benefit from its passports, its currencies, its mobility. And that’s exactly why I have to speak. Because today, colonization rarely looks like violence. It looks like opportunity. It looks like foreigners arriving with stronger currencies, raising prices, reshaping communities, and calling it development. It looks like sacred places turned into backdrops for self-realization. It looks like Costa Rica, Tulum, Atitlán, Bali — not being invaded, but consumed. The empire no longer needs to rule territories. It rules value. And the dollar is not neutral. It is a force. When we price life, healing, and worth in a currency born from extraction and war, we carry that history with us — even when our intentions are good. My fear is not that people are greedy. My fear is that we’ve normalized a system where earning ten thousand a month is called success, while entire cultures are priced out of their own land. This is not about guilt. Guilt changes nothing. This is about responsibility. Responsibility means asking: Who pays the invisible cost of my freedom? It means slowing down. It means redistributing, not just consuming. It means creating systems where value circulates locally, not only upward and outward. We cannot heal the world with the same logic that broke it. And we cannot pretend to be awake while outsourcing the consequences of our comfort. The work now is not to escape the system, but to interrupt it — with humility, with restraint, and with structures that actually nourish life. This is not a call to be perfect. It’s a call to grow up.

1 like • 11d

Hi! Thanks for your post. And it made me think about something I noticed back in 2014, while I was working on a project in Rwanda. If I went to their local market with 10 euros I can buy sooooo much real products (eggs, vegetables, meat, ext) It felt weird that everything was so cheap relative to the euro, it felt like stealing in some way. Then I did the math (an estimate) and I saw that if someone from Rwanda came to Greece with their equivalent of 10 euros (in their currency) they could buy, perhaps a potato or two. The difference was enormous. Then I started researching to understand how this is the case and why. Colonialism never stopped extracting resources for as cheap as possible, it changed the way it does it. How money is created and distributed through loans is like a game of hot potato, the ones that use it first extract most of the value, and eventually we give paper and promises and get back real resources. This is what some countries in west Africa started to react to a couple of years ago, but of course the media didn’t really show us much about that. Extraction and exploration is unfortunately built into the money system itself.

Open The Eye of Gratitude

Open the eye of gratitude. Surround yourself with people that you love and love you back, your heart will know which ones those are. Don’t erase, but set boundaries with codependent/toxic relationships, your gut will know which ones those are. Speak your truth with integrity but be willing to be misunderstood and judged. Stay silent until you hear your own voice with clarity. “Nothing is more holy than the integrity of one's own soul.” Don’t be afraid of your own mind because you will be with it until you die. As your mind is holy the mind of others is also holy. Be as honest as you can, don’t pollute other minds with lies, but remember that some things, if spoken, lose their meaning. Others are not your master or your slave, just co-passengers on a rollercoaster with fears and dreams, just like you. Most ideas are defined by their opposite, map out the polarities to find balance. I’m trying to find balance, but it’s hard, the pendulum always swings and the 0 point is an asymptote. But it’s the only way to live in concord with others and nature, A common agreement to try to sustain balance. Don’t expect others to see the world as you do, You have to try to respect others even when you don’t understand them. The most revolutionary thing you can do is “Love your Enemy.” You and I are ‘lucky’ to be alive. Because there is a past we are here, because we are here the future is uncertain, it’s true if we like it or not. Your heroes and ideals are invented. If you believe they exist, they can become your worst judge. They are only meant to guide you towards a place that is not a destination. Don’t expect or want anything from the world. Just let your heart aim towards a direction, start walking and be grateful for whatever comes your way. Trust the process, trust yourself, trust G_d. There is always movement, As there is something that contains all movement. There is something infinite in a moment, as there is something finite to a whole lifetime. Who you are is the only question you can answer.

Doing business spiritually vs Doing spirituality as business

Majority of my work today is as a personal strategic advisor to mission-driven founders. Many of them operate in the creator economy, and a subset have leaned into spirituality. Sometimes from genuine personal conviction, sometimes as a differentiator in their field. That’s led me to reflect on an important distinction. Doing business spiritually means letting your values shape how you work: your ethics, boundaries, and responsibility toward people. The aim is to help others become clearer, more grounded, and more capable over time. Doing spirituality as business is when spiritual experience itself becomes the product. Personal revelations, “transmissions,” or belief systems and practices are packaged and sold. The issue isn’t intention. It’s that spirituality is deeply personal and doesn’t translate cleanly between individuals. As guidance, it often creates confusion rather than clarity. And as a business model, it tends to be fragile, hard to sustain, hard to scale, and rarely built for long-term value. My current conviction is simple: Let spirituality be the operating system, not the product. Build things that are grounded, verifiable, and genuinely useful, while carrying the sacred with humility, not commercialization. Curious how others in this community, where spirituality is a frequent theme, see this distinction.

1 like • 13d

Hi Pontus. Thanks for your post. I feel you’re raising a very important point. Personally I always valued integrity as a important principle to help navigate this world, “nothing is more sacred than the integrity of one’s own soul”, and integrity is a very personal thing. At the end of the day I could be a master manipulator and fool everyone, but deep inside I would know the Truth. So I think everyone is responsible for their own integrity and discernment in this. And because reading your post coincides with a little healthy confrontation I had I would like to mention 3 different kinds of situations that I have encountered. One is my aunt (that has passed away), it was a family tradition to take away ‘the evil eye’ (xematiasma in Greek). My grandmother had it, then my aunt had it, it was never officially passed on to me, but some weird things have happened so it seems it kind of passed on to me. In this tradition, you can never accept money, actually it’s not good to even accept a ‘thank you’. My aunt had people come to her from far away, and would travel just to see her, but she never glamorised anything, would hardly mention it. Then the second case is one guy I met in Greece, that works with ancient Greek mystery school (similar tradition with ancient Egyptian mystery schools). Things started quite spontaneously for him and he started doing one on one sessions. The demand through word of mouth started increasing and he was taking more and more time from his day job to do this work (without charging). That slowly lead to a situation that he could even pay his rent, so as he said, he asked his ‘guides’ if he can charge something reasonable. They said yes, so he started charging small amounts just to be able to pay his expenses. Then with no advertisements what so ever it started blowing up, and he started a school and teaching groups. The course was 3 years long and had a lot. He doesn’t really have social media and actually doesn’t speak English, he is very low key on purpose. I personally was skeptical with him for years to be honest, last year I had a one on one season and I told him the truth. That I have been questioning his validity for a long time, that maybe he is lying to everyone and does it for the money ect. I confronted him on purpose to see how his ego would react. He didn’t even flinch, I could feel him as calm and collective as always and he simply said: “that is very good, because if people just believe what ever I say they don’t learn how to discern for themselves, and if they just close the door and disbelieve everything I say, again that is ok because they have every right to fo so.” That answer I can trust.

1 like • 12d

Hi @Pontus Stjernfeldt Sorry for the long rant I sent the other day. That incident I mentioned was fresh in my mind and I went into a rant. I mentioned 3 different situations that I have encountered to make the point that it seems to depend on the integrity of the person, and that is always tricky to tell from the outside. I have been thinking a lot of what you wrote, it’s been a subject on my mind for some months now. I have been working on an art project about a symmetrical 13 month calendar for about 3-4 years now. Recently I started to make it public. I’m currently focusing on the writing, drawing ext and trying to not think much about any monetisation at the moment. And I haven’t completely concluded if and how I should monetise any aspect of the project. What you wrote hit a nerve, still feel reluctant in making this into a ‘ product’, maybe a non-profit / foundation is a better structure, open and free to everyone. I still don’t know. Im also writing a book about all this, that would probably take an other year. That is a tangible product, a book some one can buy and read. I do find all this tricky to navigate to be honest. I would like to know more about what you do and I appreciate you raising this issue. But maybe the comment section is not the best way to communicate. If you feel like it you can reach out to met via email at. [email protected] Hope this message finds you well. ✌️🌍🌞

1-10 of 69

@alexandros-dimitriadis-9212

Name: Alex, Live: Athens, Greece Like: Filmmaking, drawing, land art, writing, hiking, camping, designing, building. ✌️🌞

Active 1d ago

Joined Sep 25, 2025

Athens, Greece

Powered by