Write something

Climate Eductation in schools

The Climate Majority Project has created a video about the complexity of educating children about the crisis. It is hard-hitting and shows how this subject is both depressing and demoralising, yet so very essential. Children want to understand what is happening, how we got here, and why we are doing what we are doing about it. The more people know, the more willing they are to take action, either by voicing their concerns, pressuring (empowering) politicians to act, putting themselves forward for leadership roles, or building businesses that address the issues we face. We need more information so we know what is going on. We need more people taking leadership positions. That is what this group is about - The path thorugh Education to leadership.

When the cleaners disappear

This year, I travelled to Hamilton Island in Australia to see what was left of the Great Barrier Reef. I expected to see a mix: areas of healthy reef, patches of bleached coral, confused fish moving between them. Instead, what we found looked like a lunar landscape. The reef was dead — reduced to rubble and dust on the sea floor. There were a few corals left. Around them swam a few dozen brightly coloured fish. My kids didn’t know this wasn’t normal. They were delighted. I watched them, feeling distraught, horrified, and quietly terrified. In that overheated water, with the air hot above us and sea levels rising, I had a sudden thought I couldn’t shake: this might be the last time I ever see a coral reef. I took photos with a cheap underwater camera and had to wait weeks for them to come back. When they did, they were blurred and dull. I tossed them aside — too depressing to look at. A couple of days later, something clicked. The photos weren’t poor quality. They were accurate. The water was full of particles. The sea floor really was that dull grey-green. Without the coral — and the billions of organisms that live within a healthy reef — nothing was cleaning the water anymore. Dirt, dust, organic matter, all suspended. The system had lost its workers. Years earlier, while training as an architect, I worked on a project designing an oyster-farming community on the Norfolk coast. As part of that, I learned how oysters work — and how astonishingly effective they are at cleaning water. The Norfolk coast once held billions of oysters. For centuries they were cheap food, eaten in huge quantities by Londoners. As stocks were over-exploited, numbers collapsed. Oysters went from poor man’s food to luxury — but something else disappeared too. Billions of tiny workers stopped cleaning the sea. Water quality declined. Life retreated. Now, in the UK, in New York, and elsewhere, people are trying to bring oysters back — not just as food, but as function. To restore water quality. To allow ecosystems to recover. To let life return to places that have slipped into dead zones.

🦪 Oysters: The Quiet Workers Cleaning Our Seas

1. Once upon a time, the water cleaned itself. Before we dredged, polluted, and overharvested our coasts, oysters formed vast reefs along shorelines like Norfolk’s. They weren’t just food. They were infrastructure. Each oyster filtered litres of water every hour, quietly removing excess nutrients and particles. Clearer water meant healthier seagrass, more fish, and resilient coastlines. The system worked — without machines, chemicals, or management plans. 2. Then we removed the cleaners and blamed the water. As oyster populations collapsed, the water turned murkier. Algae blooms increased. Biodiversity dropped. We responded with treatment plants, restrictions, and expensive fixes — all while missing what had changed. The problem wasn’t just pollution. It was the loss of the living system that handled pollution. We didn’t just lose oysters. We lost a function. 3. Now we’re learning how to let nature do the work again. The Norfolk oyster restoration project isn’t nostalgic — it’s practical. By restoring oysters, we restore a process: filtration, balance, resilience. The oysters don’t argue. They don’t need incentives. They just get on with the job, every hour of every day. Sometimes the most advanced solution isn’t new technology — it’s remembering how the system used to work, and stepping out of the way. Why this matters This isn’t just a story about oysters. It’s a reminder that many of our environmental “problems” are really missing systems. When we restore the system, the benefits cascade. Here is someone restoring oysters that once numbered in the millions off the Norfolk coast in England. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2025/dec/21/norfolk-coast-oysters-project

Financial inequality fuels Climate Change.

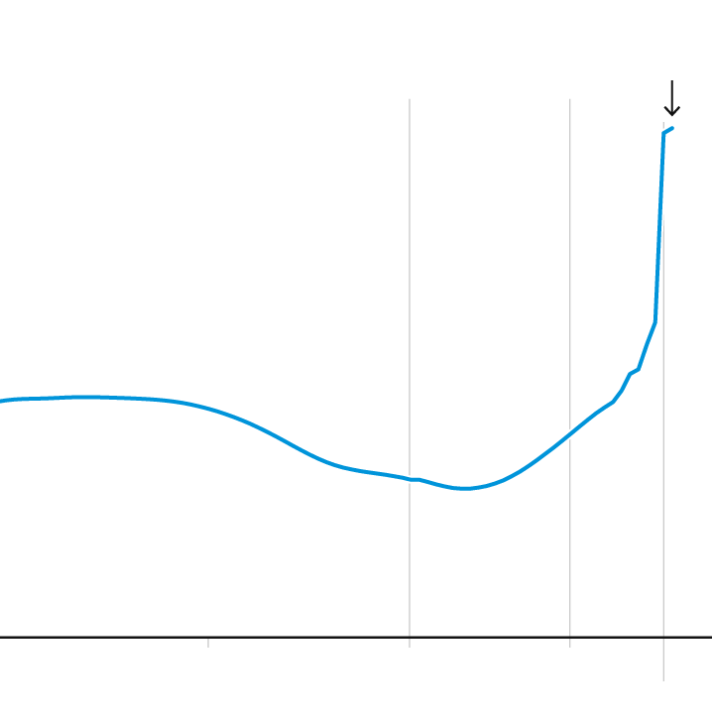

Guardian Article here Read my analysis of the growth of Billionaires. What conditions are required for a person to accumulate billions and how it is the systme that needs to change. You can find it here Read also why this is a climate issue here. Image credit: Guardian graphic. Source: World Inequality Report 2026, Arias-Osorio et al 2025, Chancel et al 2022 and wir2026.wid.world/methodology. Note: inflation adjusted annual growth 1995 to 2025

3

0

⚙️ New Lesson: Battery Types Compared

From lithium cells to sand, water, and even gravity, there’s more than one way to store energy. Each battery type has its own strengths, weaknesses, and environmental impact. This lesson breaks down how the main technologies work, what they’re made from, and where they fit in the energy puzzle. 👉 Find it here.

1-19 of 19

powered by

skool.com/has2bgreen-3767

Learn, act, and lead on climate change: from basics to advocacy to real-world action. A global hub for solutions, stories, and change-makers.

Suggested communities

Powered by