2d • Beef

Anatomy of the Bark, Mastering the Surface Science of BBQ

In the world of professional barbecue, the "bark" is the definitive signature of a master pitmaster. It is the dark, flavorful, and textured crust that forms on the exterior of smoked meats. While it may appear charred, true bark is actually a complex chemical achievement—the result of the Maillard reaction, smoke polymerization, and controlled surface dehydration.

Understanding how to engineer this crust on different proteins is what separates a standard cook from competition-level barbecue.

The Science of the Crust

Bark is not merely burnt seasoning. It is formed when the dry rub, meat proteins, smoke particulates, and rendered fats combine during a long, slow cook.

- The Maillard Reaction: This is the chemical reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars that gives browned food its distinctive flavor. In the smoker, this reaction happens slowly over many hours.

- Smoke Adhesion: Smoke is a collection of solids and aerosols. These particles stick to the tacky surface of the meat, eventually "setting" into a hard pellicle.

- The Role of the Stall: The stall—the period where evaporative cooling stops the internal temperature from rising—is actually the most critical time for bark development. As the surface "sweats," the moisture dissolves the rub into a slurry that eventually dehydrates into a crunchy crust.

Brisket: Engineering the Shattery Bark

A brisket bark should be bold, dark, and almost shattery. Achieving this requires a specific strategy:

- Coarse Seasoning: Use high-granule salt and coarse-ground black pepper. Fine powders create a "mud" that can block smoke penetration; coarse grains provide a gritty surface for smoke to latch onto.

- Airflow Management: Constant, clean airflow is essential to dehydrate the surface. If the air in your pit is too stagnant, the bark will remain soft and mushy.

- Timing the Wrap: If you use the Texas Crutch (foil or paper), ensure the bark is fully set first. If you wrap before the bark is firm, the trapped steam will wash away your hard-earned crust.

Pork: The Sugar and Fat Balance

Bark on a pork butt or shoulder is typically sweeter and stickier than brisket bark due to the higher sugar content in pork rubs.

- Caramelization: Sugars in the rub begin to caramelize and darken during the long smoke. However, if the pit temperature exceeds 300°F, these sugars can burn and become bitter.

- Surface Prep: Pat the meat completely dry before applying your rub. Any excess surface moisture will delay the Maillard reaction and can lead to uneven bark formation.

Chicken: The Quest for Crispy Skin

Unlike red meats, the "bark" on chicken is actually the skin itself. The primary challenge here is preventing a rubbery texture.

- Moisture is the Enemy: For the crispiest skin, allow the chicken to air-dry in the refrigerator for at least an hour before seasoning.

- The Temperature Spike: While brisket and pork thrive at 225°F, chicken skin often needs a higher temperature—up to 325°F or 350°F—near the end of the cook to render the subcutaneous fat and crisp the skin into a flavorful crust.

Mastering the Finish

Achieving a flawless bark takes practice and a deep understanding of your specific smoker's characteristics. Pros learn by observing the transition from a wet surface to a tacky one, and finally to a hardened crust.

1

0 comments

powered by

skool.com/bbq-beer-and-whiskey-9787

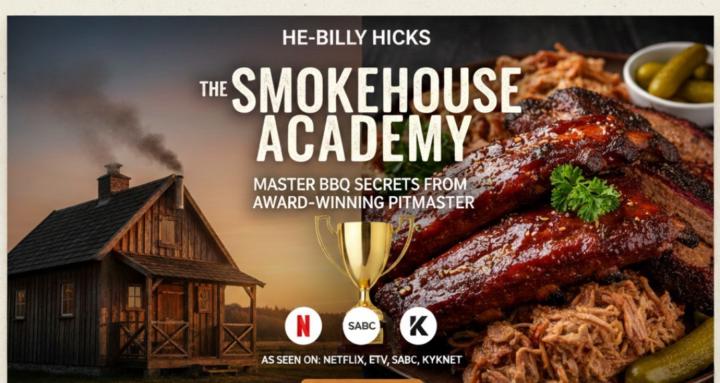

Award-winning pitmaster teaching BBQ, craft beer & whiskey-making. Join He-Billy Hicks' community of makers. Level up your craft. As seen on tv

Suggested communities

Powered by