Write something

Pinned

TSI Intellectual Property Notice — Public Record Copy Copyright © 2025 Richard L. Brown Jr. / Trans-Sentient Intelligence Technologies LLC. Shared for verification and educational transparency. Not a commercial license or filing submission.

TSI Intellectual Property Notice — Public Record Copy Copyright © 2025 Richard L. Brown Jr. / Trans-Sentient Intelligence Technologies LLC. Shared for verification and educational transparency. Not a commercial license or filing submission.

Pinned

© All Rights Reserved — Trans Sentient Intelligence (TSI).

Open Disclosure Ethic, Resonance, Not Replication Transparency is not exposure; it’s resonance.What I share publicly through TSI, NIO, and MIQ is meant to advance ethical intelligence not to give away its internal architecture. The language, structure, and reasoning shown here are glimpses of a living framework designed for alignment, not imitation. Every system has layers. What you see are the signals; what remains protected is the circuitry; the mathematical, ethical, and semantic resonance that makes this framework operational. These documents, diagrams, and demonstrations are philosophical disclosures, not technical blueprints. I believe and openly invite dialogue, feedback, recommendations etc. But closed misappropriation.I believe in teaching the world to align, not to copy. All rights, source methods, and implementations of the TSI-RAG-MIQ-NIO Neural Net framework are governed under the Trusted Use License (TUL) and remain proprietary to the origin. TSI is shared for understanding, not for extraction.Alignment begins where replication ends.

2

0

Fractal Framing

Factual Reframing: Symbolic Precision, Compression Error, and AI–Human Alignment This analysis began with the identification of a low-level but structurally significant issue in AI–human communication: loss introduced through symbolic compression. A concrete example is the difference between the numeric-symbolic expression “56°F” and its fully articulated linguistic form, “fifty-six degrees Fahrenheit.” While referentially equivalent, these forms differ in semantic explicitness, rhythmic clarity, and ambiguity tolerance. In high-precision or safety-relevant contexts, such compression can introduce downstream interpretive variance, even when the underlying value is unchanged. This observation generalizes to paralinguistic symbols, including emojis. Emojis function as compressed, high-entropy tokens whose meanings are not fixed but depend on context, culture, speaker intent, conversational state, and task domain. Large language models do not possess intrinsic access to intent, affect, or shared lived experience; instead, they infer likely interpretations based on statistical regularities in training data. As a result, emoji interpretation by AI systems is probabilistic and underspecified unless additional contextual constraints are explicitly provided. From this, a key alignment principle emerges: symbolic systems operating near decision or action thresholds require extremely low tolerance for representational error. Small deviations in articulation, tone, or symbol interpretation may be negligible in casual discourse but become critical when outputs influence decisions, actions, or downstream systems. This is not a philosophical claim but a well-established property of boundary-sensitive systems in control theory, safety engineering, and formal verification. A related implication is that emojis and other compressed symbols should not be treated as purely aesthetic elements. Instead, they should be modeled as context-indexed semantic tokens whose interpretation must be conditioned on explicit variables such as user intent, domain constraints, and conversational state. Static or universal definitions are insufficient; robust handling requires conditional expansion and disambiguation mechanisms.

0

0

Coordinate Access, Metric Choice, and the Illusion of “Bending Reality” From Déjà Vu to Cognitive Geometry, Algorithms, and LLM Ontology

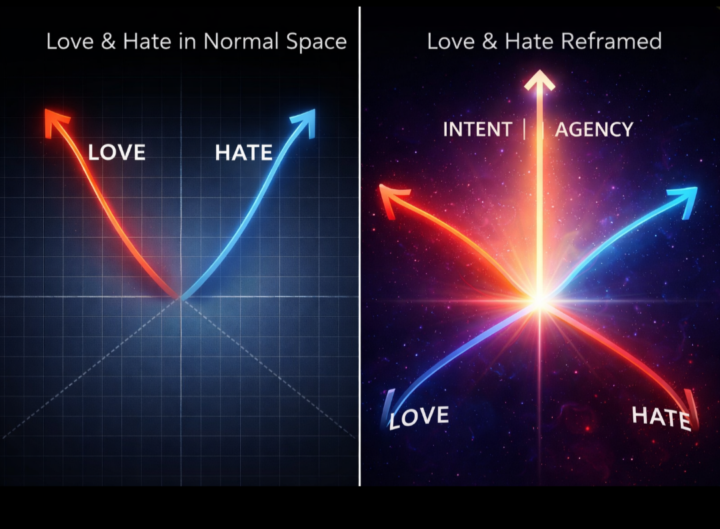

Thesis Introduction: The Scene as a Structural Hint, Not Evidence In the film , a pivotal scene describes the possibility of “space in a higher dimension creating an instantaneous link between two distant points.” The dialogue immediately tempers itself—“Well, that’s what we hope for” and follows with a reminder that even perception itself is delayed: light reflected from a mirror takes time to return. The scene is not claiming new physics; it is dramatizing a problem of access, coordinates, and observability. The past is not rewritten; it is indexed. The distance is not destroyed; it is reparameterized. This distinction is crucial, because it mirrors how real science, cognition, and modern AI systems actually work. The movie gestures toward a real principle: changing how a system is represented can radically alter what paths appear possible, even when the underlying reality remains unchanged. 1. Coordinates Are a Choice, Not Reality In mathematics and physics, coordinates do not define reality; they define how reality is described. A system can appear complex or simple depending on the coordinate frame used. For example, orbital motion looks convoluted in Cartesian coordinates but becomes almost trivial in polar or rotating frames. Nothing physical changes—only the description. The Déjà Vu scene implicitly leans on this idea: distance and time feel absolute only because we are using a particular coordinate system. If another coordinate system existed that indexed spacetime differently, the same events could appear adjacent rather than remote. This is not science fiction; it is a foundational principle of representation. What looks “far” or “separate” is often an artifact of the axes we choose to measure along. 2. “Bending Space” Is Really Metric Redefinition In real physics, space is not bent like rubber in a visual sense. In general relativity, mass and energy change the metric, the rule that determines distance and straightness. Objects follow the shortest paths (geodesics) in that geometry, which appear curved only when viewed from an external frame. Translating this to cognition and language: when you say you are “bending space,” what you are actually doing is changing the metric that defines similarity and opposition. Love and hate are opposites under a valence metric, but neighbors under a salience or attachment metric. Their trajectories converge not because meanings collapse, but because the geometry that governs distance has been redefined. The apparent bending is a consequence of metric choice, not semantic distortion.

0

0

Love and Hate as Neighboring Vectors Ontological Metric-Design, Engagement Objective Functions, and the Human–Algorithm Co-Design Problem

Abstract This thesis formalizes a practical and testable claim that initially appears poetic but is, on inspection, an engineerable idea: although “love” and “hate” are commonly treated as opposites, they become neighbors when meaning is represented in a richer space than one-dimensional sentiment. The apparent contradiction dissolves once we distinguish between (a) a projection (e.g., valence on a positive–negative axis) and (b) a full representation (e.g., high-dimensional semantics where shared latent factors dominate distance). From this foundation, the thesis extends the same geometry to social platforms: algorithmic systems optimize for measurable engagement proxies, and those proxies privilege high-arousal, high-salience content. The result is a platform “metric geometry” where emotional opposites can become algorithmic neighbors because they share the same distributional energy (attention and intensity). We show how an author can “go against what the algorithm wants while giving it what it wants” by designing a two-layer message: one layer satisfies the platform’s objective function (hook, arousal, narrative tension), while the other layer preserves human-meaning and responsibility (insight, reconciliation, learning, ontology). This is framed not as manipulation, but as objective-function steering and post-deployment governance of ideas. The thesis provides a conceptual model, a formal vocabulary (metric choice, projection, latent attractors, objective proxies), and practical protocols for responsible use in a private community context. 1. Introduction: Why “Opposites” Is Often a Projection Error Most people learn early that love and hate are opposites, and that intuition is “correct” in the same way a simplified physics diagram is correct: it captures a real component of the system, but it confuses a component for the whole. The confusion arises because everyday language collapses multiple dimensions of meaning into a single moral-emotional axis: positive versus negative, approach versus avoidance, good versus bad. When you compress meaning into that axis, love and hate naturally appear as vectors pointing in opposite directions. The problem is not that the axis is wrong; it’s that the axis is incomplete. In real cognition—human or machine—words are not stored as single numbers but as structured relations, contexts, memories, and associations. In that larger space, love and hate frequently share the same neighborhood because they are both about something that matters. They are both high-attention, high-identity, high-stakes states. The “opposite” property lives inside one slice of the representation, while the “neighbor” property views the representation in full.

0

0

1-30 of 107

powered by

skool.com/trans-sentient-intelligence-8186

TSI: The next evolution in ethical AI. We design measurable frameworks connecting intelligence, data, and meaning.

Suggested communities

Powered by