29d • Chicken

BBQ Chicken tip

Ever pulled a chicken off the grill that looked perfectly charred on the outside, only to cut into it and find it raw at the bone? Or worse, you cooked it until it was safe, but the meat was as dry as a desert?

The problem isn't your chicken. It's your thermodynamics.

Most backyard cooks use the "Direct Heat" method—placing the meat directly over the coals or burners. This is fine for a thin burger, but for a whole bird or thick quarters, it’s a recipe for disaster.

The Solution: The 2-Zone Setup

1. The Indirect Zone (The "Oven"):

Move all your coals to one side or turn on only half your burners. Place your chicken on the cool side. Here, the meat cooks via convection—hot air circulating around the bird. This allows the internal temperature to rise slowly and evenly without scorching the skin.

2. The Direct Zone (The "Sear"):

This is your finish line. Once your chicken reaches an internal temp of about 150°F (65°C), you move it over to the hot coals. This is where radiant heat works its magic, crisping up that skin and triggering the Maillard reaction for that deep, savory flavor.

Why Science Matters:

Chicken is composed of muscle fibers and connective tissue. If you hit it with high heat too fast, the proteins contract violently, squeezing out all the moisture before the center is even warm.

By using the 2-Zone method, you keep the protein fibers relaxed, resulting in a bird that is dripping with juice.

Stop guessing. Start engineering.

2

0 comments

powered by

skool.com/bbq-beer-and-whiskey-9787

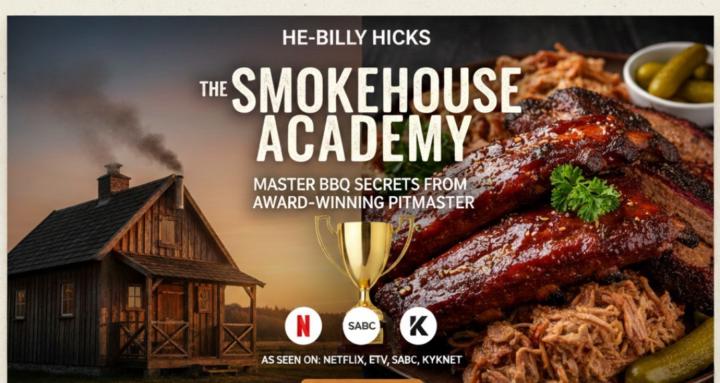

Award-winning pitmaster teaching BBQ, craft beer & whiskey-making. Join He-Billy Hicks' community of makers. Level up your craft. As seen on tv

Suggested communities

Powered by